Jean-Marie Mayeur and Madeleine Reberioux, The Third Republic from its Origins to the Great War, 1871-1914 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984), pp.,101-115.

Religious Belief in the 3rd Republic

The first decades of the Third Republic saw only limited economic and social change. As we have already said, the growth of the economy was much more rapid on either side of the period which runs from Thiers to Meline. The relative importance of the various social groups hardly altered. But what about modes of belief, of thinking, of feeling? What about levels of education and cultural ideals? The reply to this series of questions is all the more difficult to provide if we want it to apply not only to the culture of the elites but also to that of the various social groups. However, the effort is worth making, since after all the ambition of the founders of the Republic was, by the secularization of society and the development of education, to finish with traditional beliefs and systems of values and to develop the ideas of enlightenment and progress. In this sense the republicans, even if they did not think of changing the relations between the social classes, wanted to transform the appearance of French society. To outline the successes and failures of their ambitions is to spotlight the areas of resistance, the confrontations and the challenges. Whether we describe the forms and evolution of religious feeling, the systems of education, the penetration of popular circles by the dominant cultural patterns, or the literary and artistic creations, we shall discover permanence, innovation and anticipation. . . .

Beliefs and unbelief

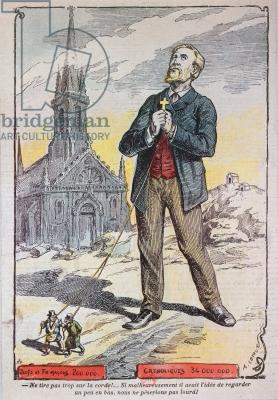

The religious attitudes of the French demand a very fine analysis. Does France remain 'catholic France', the 'eldest daughter of the Church' because the vast majority of the population is baptized? The defenders of the Chu rch thought she did, and they attributed the misfortunes of the times to the plots of a minority of freemasons, Jews and Protestants.

Certainly attachment to the major rites of Catholicism which form the landmarks of life was incontestable. And Christianity was deeply rooted in the nation; after all, the dominant morality, the very morality disseminate by the non-denominational school, was the laicized form of the morality taught by the Church since the beginning of the modern age. These substantial facts, too often forgotten, explain the illusion of those who held the 'plot' theory. Nevertheless, these people forgot the fundamental fact which numerous contemporary observers - Taine,1 for example - perceived: the differing intensity of practice and fervour. . . .

Thus the city, a modern Babylon which the Church distrusted, was the citadel of religious indifference. The de-Christianization of Paris has been studied recently on the basis of baptisms, marriages and funerals.4 The trend accelerated sharply after 1875; there was a fall in the number of baptisms and a rise in the number of civil marriages and burials. Among the urban classes, the workers were particularly indifferent to religion.... There were complex reasons for it. Anti-clerical traditions went back to the French Revolution and sometimes beyond it to the world of craftsmen. That the Church which had always preached resignation to the poor and almsgiving to the rich compromised itself with the 'authorities' counted for just as much. We still need to know what effect this 'scandal' had on the workers and how it influenced their behaviour where religion was concerned. No doubt one must allow for the indifferent knowledge of the working-class world possessed by a clergy of rural origins. Moreover, the parishes were huge and the priests badly distributed. In 1877 the parishes of Saint-Ambroise and Saint-Joseph in the faubourg Saint-Antoine had 66,000 and 54,000 inhabitants respectively.5 The rigidity of the framework laid down in the Concordat and the passivity of the public authorities made the creation of new parishes very difficult. Not only was the organization poorly adapted to meet the needs of the situation; so was the language of the priests. They lived the life, spoke the language and often adopted the moral code and system of values of the bourgeoisie of notables who had attended church more regularly since the middle of the century.

The religious evolution of the bourgeoisie was complex. While the old bourgeoisie, once disciples ofVoltaire [the symbol of Enlightenment skepticism], had partly returned to the Church, especially in the provinces, the 'new strata' of the bourgeoisie were indifferent if not hostile to a Church which, since the Syllabus and the Council, seemed ever more profoundly alien to the spirit of the century. It needed the new atmosphere that became apparent after 1885 to produce a change. Some of the elites began to have doubts about science and progress, while in Rome Leo XIII adopted a different tone when he spoke about the modern world. There were resounding conversions in the intellectual world, Catholicism began to enjoy growing prestige among young people and the notion of Christian democracy had considerable success - as we shall have occasion to repeat - among the working population. These aspects of the situation at the end of the century cannot be omitted from the picture.